Ignore the Spores

Replacing spores with tendrils in The Last of Us

***Spoilers for The Last of Us on HBO Max***

The Last of Us has been heralded as one of, if not the best, video game adaptations ever made1,2. Countless side-by-side comparison videos of the show and the game showcase the attention to detail and devotion to the source material present in the HBO adaptation. That is not to say the show is a perfect one-to-one remake of the game; television is, after all, a different means of engaging with the material than actively participating in gameplay.

By and large, however, the mechanics of cordyceps infection have largely been preserved in the HBO adaption. There are multiple stages of cordyceps infection, beginning with “runners”. Runners are recently infected, retaining their human appearance while indiscriminately attacking any uninfected they encounter. Over time, runners progress into various other forms including stalkers, clickers, bloaters, shamblers, and, a truly disgusting sounding phase, rat kings. Eventually, infected die and cordyceps consumes the rest of their tissue, fusing them in place as the fungus spreads around them. In the game, as cordyceps grows around the dead infected it forms fruiting bodies that release infectious spores. This mirrors real-life cordyceps infection in ants, in which the fungus compels the ant to latch onto foliage and fuses it in place before a stalk sprouts from the carcass’s head to release cordyceps spores.

Spores are a key component of the fungal life cycle. Many variations of spores exist and are produced either sexually or asexually3. Spores are dispersed in many ways, including passive airflow, active ejection from fruiting bodies (for example, mushrooms), in water, or as passengers on other organisms such as insects3.

We are constantly exposed to airborne spores. Fungal spores are found both indoors and outdoors throughout all seasons4. It is difficult to estimate how far spores can travel through the air, but different varieties of spores can be found meters to hundreds of miles from their source4. One of the most common airborne pathogenic fungi in humans is Aspergillis fumigatus5. Aspergillis is an opportunistic pathogen; that is, even though we breathe it in regularly it does not cause disease in most people. Aspergillis requires an opportunity to cause disease in susceptible hosts, such as the immunocompromised or those with underlying health conditions. Inhalation of Aspergillis spores can result in allergic reactions, infections, or even pneumonia-like disease in the lungs6,7. Researchers have recently found that Aspergillis fumigatus produces its own fungal secretions that redirects the host immune response, resulting in tissue damage in the lung over repeated exposures5.

As spores are needed for successful reproduction and dispersal of fungi they have evolved to survive a variety of inhospitable conditions4. Airborne spores often dry and become dormant, waiting to germinate in suitable growth conditions3,4. Dormant Aspergillis spores have been found to survive for up to one hour at 50°C (122°F) and can withstand UV radiation3. Spores from some yeasts can endure even more extreme temperatures and are resistant to UV radiation, high pressure, and drought3.

In the game, whenever characters encounter cordyceps spores they don gas masks to prevent infection through inhalation. This poses a problem for the HBO adaptation, since, as The Last of Us writer and co-creator Neil Druckmann says, “…maybe the most important part of the journey is what’s going on inside behind their eyes, in their soul, in their beings.”8 Rather than having the actors continuously put on and remove masks, the writers and creators chose to use a different feature of fungal morphology to heighten the stakes of cordyceps: tendrils.

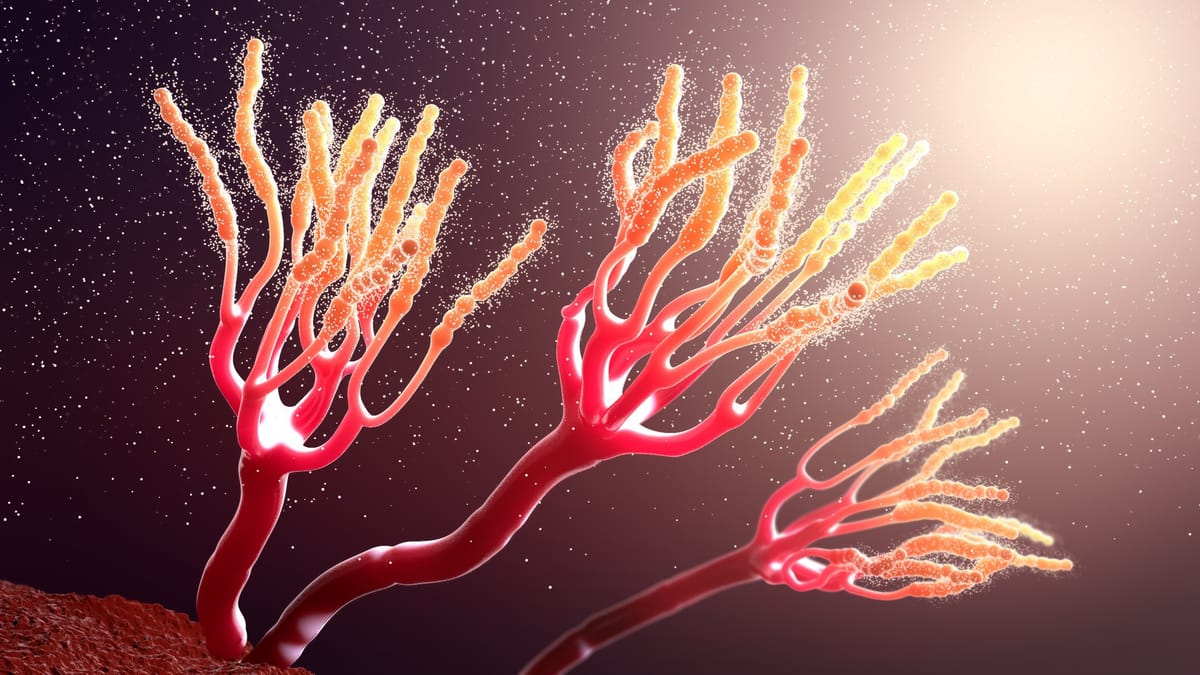

Tendrils, or hyphae, grow in root-like networks to form mycelium which The Last of Us uses to great effect. Visually, the tendrils underscore the invasive nature of cordyceps as they wave from the mouths of infected in a macabre display. Tendrils also add an extra layer of tension to living in this post-apocalyptic world because, as we learn in episode 2, “The fungus also grows underground. Long fibers like wires, some stretching over a mile. You step on a patch of cordyceps in one place and you can wake a dozen infected somewhere else. Now they know where you are, now they come.”

Imbuing the infected with a cordyceps-linked hive mind is an extension of underground communication matrixes that hyphae and plants form in nature, called mycorrhizal networks9. Mycorrhizal networks connect multiple species of plants and fungi to share nutrients and influence plant behaviors through defensive signaling, fungal colonization, root growth, and photosynthesis rate9,10. This communication is thought to be mediated through biochemical signaling9. A 2022 study found that fungi produce electrical impulses that travel through mycelium, similar to those observed in the central nervous system, and that these impulses compose a language through which fungi can communicate11.

In real life if you step on a patch of moss a herd of mushrooms won’t come charging after you. But these connections really do lie just beneath our feet; a sophisticated network of plant and fungal life that has evolved to form cooperative bonds that we are just beginning to understand.

References

1. Kelly S. The Last of Us review: 'The best video game adaptation ever'. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20230109-the-last-of-us-review-the-best-video-game-adaptation-ever. Published 2023. Updated 1/10/2023. Accessed 2/23/2023.

2. Lawler K. Review: HBO's 'The Last of Us' is the best video game adaptation ever. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/tv/2023/01/15/hbo-the-last-of-us-review-best-video-game-adaptation-ever/11031858002/. Published 2023. Updated 1/15/2023. Accessed 2/23/2023.

3. Wyatt TT, Wösten HAB, Dijksterhuis J. Chapter Two - Fungal Spores for Dispersion in Space and Time. In: Sariaslani S, Gadd GM, eds. Advances in Applied Microbiology. Vol 85. Academic Press; 2013:43-91.

4. Segers FJJ, Dijksterhuis J, Giesbers M, Debets AJM. Natural folding of airborne fungal spores: a mechanism for dispersal and long-term survival? Fungal Biology Reviews. 2023;44:100292.

5. Okaa UJ, Bertuzzi M, Fortune-Grant R, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus Drives Tissue Damage via Iterative Assaults upon Mucosal Integrity and Immune Homeostasis. Infect Immun. 2023;91(2):e0033322.

6. Barnhart M. WHO releases list of threatening fungi. The most dangerous might surprise you. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2022/10/26/1131602076/who-releases-list-of-threatening-fungi-the-most-dangerous-might-surprise-you. Published 2022. Accessed 2/15/2023, 2023.

7. Aspergillosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/aspergillosis/index.html. Published 2022. Updated 12/27/2022. Accessed 2/28/2023, 2023.

8. Carpenter N. Why The Last of Us creators swapped spores for Cordyceps networks. Polygon. https://www.polygon.com/entertainment/23562421/last-of-us-cordyceps-spores-tv-show-hbo. Published 2023. Updated 1/22/2022. Accessed 2/27/2023, 2023.

9. Gorzelak MA, Asay AK, Pickles BJ, Simard SW. Inter-plant communication through mycorrhizal networks mediates complex adaptive behaviour in plant communities. AoB Plants. 2015;7.

10. Figueiredo AF, Boy J, Guggenberger G. Common Mycorrhizae Network: A Review of the Theories and Mechanisms Behind Underground Interactions. Frontiers in Fungal Biology. 2021;2.

11. Adamatzky A. Language of fungi derived from their electrical spiking activity. R Soc Open Sci. 2022;9(4):211926.